The British Empire arose largely by accident. Yes, really. What actually happened was that Britain faced continual attempts at conquest by European dictators. A great many of Britain’s wars were all about national survival. As narrated elsewhere, Lord Mountjoy’s victory over the Spanish and Irish at Kinsale in 1603 was make-or-break for Britain. As with the earlier Armada invasion, Spain’s objective was the conquest and subjugation of the entire British Isles, and the wholesale massacre of everyone who refused to turn Catholic. The English weren’t imagining this. The 300 martyrs under Mary Tudor didn’t burn themselves to death. Phillip of Spain once memorably remarked that he would carry the faggots to burn his own son if he turned heretic. And because the Spanish also controlled the Netherlands, Britain was in constant peril. Anyone controlling the Scheldt estuary was in a position to launch a seaborne attack at any moment. The Great Armada of 1588 was widely expected to succeed. Thanks to Sir Francis Drake and many other dauntless sea captains – not to mention the unchancy weather – the expedition ended in disaster.

After Kinsale England made peace with Spain. All Britain wanted from the world was to be left alone in peace. Yet isolationism is seldom a viable policy. The next peril came from France, where the power-crazed Louis XIV was determined upon conquest. His deal with the Sultan of Turkey was that he would have western Europe, and Turkey could have the East. Charles II managed to keep the French at arms’ length, but war was inevitable. It came when Louis tried to take over Spain. John Churchill (later Duke of Marlborough) won decisive victories over the French at Blenheim and Ramillies in alliance with certain German princes. There was peace for a time; but the war returned in the mid-eighteenth century.

The Seven Years’ War (1756-63) was the first major colonial war. It was partly about control of India and North America; but its immediate cause was a colonial dispute about the carving-up of Poland. Austria, Prussia and Russia all wanted bits of it. This was to become a drearily familiar theme in European politics. Thanks largely to the Royal Navy, Britain was successful in defeating the French, whose colonies were annexed largely to prevent the French from having them. This is how Canada came to be British. Francophone Québec was given extraordinary privileges. French is still the official second language of Canada. (In Montreal it is the first.) The idea that foreign countries should be left alone to govern themselves is a purely modernist idea. Yes, this is what we think now. Then, self-determination would have been regarded as a delusional fantasy.

The War broke out again in earnest in 1793 after the execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. Apologists for the French Revolution are apt to smooth over the Terror. It was not just the aristos who got their heads cut off. Countless innocent civilians were also massacred, especially in the Vendée and the Loire valley. Mass torture and murder were not merely widespread. They were the instrument for ensuring compliance in the survivors. All subsequent insurgencies have studied the French Revolution carefully, and applied its lessons faithfully. Inevitably, Terror ends in dictatorship. The tragedy for Europe was that Napoleon Buonaparte was not only every bit as evil as Adolf Hitler. He was also a military genius, and a born administrator. The long, twilight struggle to defeat him took 22 years to accomplish.

The Allies came and went. The UK was plunged into debts it has never been able to repay during the war with Napoleon. Armies and navies do not come cheap. Worse, the Allies had to be bribed repeatedly to make war on France, even though it was their own survival at stake. Frequently Britain stood alone against the terrible foe. Britain yearned for peace. Unfortunately they found that peace with France was impossible. Britain offered Napoleon absurdly generous terms under the Treaty of Amiens (1802). Almost any peace, they felt, was better than war without end. Within months they realised that Napoleon was cheating them. He reduced Switzerland to slavery and kept demanding more from the supine English. With great reluctance England resumed hostilities.

Only at sea were they successful at first. Nelson and his fellow-captains won decisive victories which kept the French penned up in Continental Europe. Napoleon – like Hitler – has been called insane for his invasion of Russia. The truth is that in both cases it was stark necessity. When your empire is based on a war economy, you must keep expanding or perish. Britain denied Napoleon access to the sea. What the man really wanted was to be an Oriental emperor. His invasion of Egypt in the 1790s makes no sense otherwise. His plan was to march his army through Asia to India. Unfortunately for him, this plan was foiled by Captain Sidney Smith, a few sailors and Jazzar Pasha’s formidable Turks. They fortified Acre and defied every attempt to take it. When the plague broke out in his army, Napoleon threw his cannons into the sea and abandoned his troops. This was to be a familiar story. When the going got really tough, he always piked out and left his men in the lurch. And yet they adored him. It is a sad commentary on the essential servility of human nature.

Meanwhile Britain fought on. Frequently alone, as Napoleon continued to beat up every army sent against him. The once-mighty Prussia was reduced to semi-slavery. Often they had accepted vast subsidies and done nothing with them. The three Allies (Austria, Prussia and Russia) were at most times far more interested in partitioning Poland than fighting France. Seeing his chance, Napoleon created a Grand Duchy of Warsaw and got their matchless cavalry in return. It is hard for modern folk to conceive just how monstrous was Napoleon’s empire. Client states and outright annexations are listed in blue:

It was not merely monstrous in size. Occupied Europe was a military dictatorship in which the slightest disobedience was punished mercilessly. Until then Germans had been quiescent enough. Thanks to Napoleon’s iron rule Germany began to feel the stirring of nationalist sentiment, together with a passionate hatred of France. (Cue World Wars 1 and 2).

Wellington’s Peninsula campaign decided the war. As in WW2, the Russians claim first place in the defeat of the Great Enemy. Yet the Czar was always temporising. Sometimes he fought against France. All too often (as after the Battle of Friedland) he made a despicable peace with Boney. Nobody in Europe thought the small British force in Portugal had any hope of holding off the terrible French hordes. Yet Sir Arthur Wellesley (as he was then) had studied Napoleon’s victories carefully, and detected a weakness. Since the French advanced in columns, steady infantry in lines could bring fire to bear on the advancing columns and halt them in their tracks. If you study warfare at all, you will realise that Wellesley’s strategy and tactics are probably unmatched since the days of Hannibal.

What was more to the point was that he realised that the war against Boney was as much a moral crusade as anything else. Napoleon lied, cheated and massacred the innocent whenever he felt it was convenient. The result was that he reduced his captive Europe to a starving concentration camp. The enthusiasm with which the deluded of Europe embraced his soldiers didn’t last long. His wicked profligacy with the lives of his own men was notorious. Compare these two:

Boney showered praise on his men, who inexplicably fell under the spell of his charisma. He wasted the lives of two millions of them in his wars of conquest. In Egypt, and again on the retreat from Moscow, he shamelessly abandoned them. Wellington may indeed have referred to his troops as the scum of the earth, but no general has ever spent more pains and effort on his commissariat. His quartermaster Sir John Murray was arguably the best in history. Moreover, he was a man of his word. Many of his Spanish losses came from keeping promises made to the fantastical delusionaries of the Spanish armies. Thereafter he realised that only from Spain’s formidable guerilla bands could he gain any useful help. After Talavera he dealt solely with them, and ignored the provincial juntas.

Unlike the Spanish, the Portugese swallowed their pride and allowed themselves to be put under the command of General Beresford, who armed and trained the Caçadores in British tactics. They repaid Wellington’s trust on the ridge at Bussaco and elsewhere. Despite his cold, aloof exterior Wellington was a connoisseur of human nature. The Portugese army is worse than useless as it stands. Yet this has nothing to do with racial degeneracy. Give them proper training and weapons, and role models, and they will well repay my trust. And they did. The result was a curious dual warfare. The French raped, tortured, plundered and murdered with impunity. When locals were enrolled to guide their armies, they were routinely executed when they were of no further use. The Spanish guerillas responded in kind. Even the relatively gentle Portugese began to torture their prisoners. Yet with British troops the French were astonishingly chivalric. Since these sons of the Guillotine worshipped force and violence for their own sake, they embraced the British armies as their most successful students.

After Wellington cleared out the Iberian Peninsula and invaded France, the terrified French expected nothing less than to have all the horrors they had inflicted upon the world returned with interest. In the south, one terrified mayor hosted a dinner for the enemy officers, expecting to be massacred at its conclusion. Instead:

The Provençal French could scarcely believe it. Many wrote that they would like to be governed by these British permanently. The Highland Scots were especially cherished, and families vied to have their own kilted warrior under their roof. At least one British soldier who raped a local girl was summarily hanged. He thought it was permitted upon enemy territory. The remainder of the army learned quickly. The result was that on his triumphal march through the South of France Wellington had no need to post sentries.

Now here is a point historians appear to have overlooked. England and France had been fighting for nearly a millennium. After Wellington’s extraordinarily merciful occupation, France had no appetite for fighting against their old foe any more. Wellington’s victory was that of Christianity over barbarism. If you hear echoes of Alfred’s victory over Guthrum, then yes. So do I. Alfred’s prescription really does work. Knock the stuffing out of your barbarian enemy. At the moment they expect your final vengeance, extend your hand, and tell them: rise, friend. After the second world war, the victorious Allies realised that it was the mercy of Wellington that would bring peace to Europe, rather than the retribution of Clemenceau.

The scene: the road from Ligny towards Waterloo. Prince Blücher has already lost a pitched battle with Napoleon. He was wounded in the struggle. And the man is past seventy. The cannons are becoming bogged in the mud. And this Prussian gets down from his horse to help with the cannon, making the above memorable remark. Consider the cowardly and utterly pusillanimous behaviour of Prussia right through the the war. Yes, we will accept English gold to fight Napoleon. Then we will break every promise and hope to get some more of the mutilated corpse of Poland. Having beaten Blücher at Ligny Boney had no fear that the Prussians would come to Wellington’s aid at Waterloo. Why would the Prussians keep promises? I never do. And they never have until now. He despatched Wavre with some divisions just in case, to guard the way; but he had little apprehension of peril:

But he didn’t have it. Most of his troops were raw recruits unable to manoeuvre. Many of his best troops finished up in Battery Point, Hobart. Yet he had little choice but to stand and fight. Boney had promised his men the sack of Brussels: the usual French orgy of rape, torture, plunder and indiscriminate murder. Wellington’s generalship at Waterloo was up to his highest standards. Yet he would have been beaten without the Prussians. He trusted that Blücher would keep his word. And he did.

One of Napoleon’s many delusions was that England’s wealth came from its far-flung empire. He never grasped that on the contrary, England’s wealth came from its manufacturing. Britain cheerfully returned many of its captured colonies in a vain attempt to appease the awful dictator. Even the darkest stain on its empire (the slave colonies of Jamaica and the like) were only important to the greedy and selfish traders whose grip on the government cost tens of thousands of redcoats to yellow fever. Britain at large was not wedded to its slave colonies. When Toussaint l’Overture’s slave revolt in Haiti seized control of that island, Colonel Maitland (later the hero of Waterloo) offered Toussaint alliance with Britain. The latter accepted. Maitland was excoriated by the plutocracy, but he didn’t care. The point was that empire did not mean much to the British at the time. General Abercromby raised a dozen regiments from among the Caribbean slaves. Everyone who enlisted, he unilaterally freed. The planters howled, and Abercromby closed his ears.

Later on, as the European powers decided to divide up the world between them, Britain joined in. The White Man’s Burden became, for the first time in human history, an actual thing. And suddenly race became an issue. Europeans never cared about race before. But one thing is absolutely true. Paternalistic the British Raj certainly was. Mean? No. In the novels of John Buchan – that most broad-minded of imperialists – we see a very different world from, say, apartheid Suid Afrika. Buchan’s heroes always speak to natives in their own tongues. Davie Crawford may be the overt hero of Prester John, but the Reverend John Laputa steals the show. Persons of colour are mostly treated honourably. You may know that Paul Robeson was disgusted by his role as Bosambo in the black-and-white movie Sanders of the River. Why in that case did he accept the role? I guess it’s because he had read Edgar Wallace’s books about Sanders. Again, Sanders (and Bones) are the obvious heroes, but Bosambo is a superb character: many-sided, capable, intelligent, and utterly trustworthy in all matters of importance. To have him reduced to a pitiful Uncle Tom was a vile slander.

Parenthetically, the one great failure of Buchan’s early career concerned the Boers. After the war he was placed in charge of the Boer camps, which were in a disgraceful state. Where was Florence Nightingale when we needed her? The death rate in the camps was almost as bad as that among the British soldiers. The youthful Buchan sorted it out in short order. The British were very merciful to the Boers. Perhaps too much so. Lord Milner then charged him to find Kruger’s hidden gold. His failure to do so meant that he was forced back upon his novels and his law practice. A curious emblem of imperial cognitive dissonance is that he was actually betrayed by the man upon whom he based Pieter Pienaar in the Hannay books. Schalk Minaar’s ultimate loyalty was not to the British but to Kruger. As a result, Kruger’s gold remained with the terrible old man, and was the foundation of the apartheid state. (This story is little-known, but is related in The Buchan Papers, published after Buchan’s death.)

I should probably not need to recount the tale of the war against Hitler. It was Boney all over again. The French this time will collapse in a heap. The Russians will stab us in the back when it’s convenient. They will only fight on our side at a terrible price. Alanbrooke recounts in his war diaries that in negotiations with Stalin he realised he was in the presence of a first-rate military brain who could not be deceived, and demanded constant reinforcements sent through Arctic waters. Tens of thousands of British merchantmen lost their lives on the perilous voyages to Murmansk and Arkhangel. But in 1940, during the world’s Darkest Hour, when Churchill looked out from his bunker Britain had barely a friend in the world. Only the heroic Greeks were still fighting on. The Crete campaign was the result. Strangely enough some historians hold up the Crete campaign as an example of British incompetence. Instead it decided the outcome. While it was a defeat for us, it wasted seven weeks Hitler could not afford. And he never used paratroops again after losing 2000 of them to the civilian militia. (The Germans had, incredibly, believed that Crete would support them because they mistrusted Athens. The defiant, uncompromising Cretans soon disabused them. By the war’s end the terrified Germans had barricaded themselves in Hania.)

By 1945 the British Empire was utterly spent. A new order was arising in the world. And this was Britain’s reaction:

Not immediately. We don’t want the appalling chaos that happened when the Portugese abandoned their colonies in 1974. But in due course. Certainly. Because we never really wanted an empire. We only acquired it to save those lands from something worse.

Would it have been worse? Oh yes. Economists have drawn up a league table showing the ultimate prosperity of former European colonies. Britain scores first place. (Hurrah! Land of Hope and Glory!) Unsurprisingly, Belgium comes in last. The first to be granted independence was India. Because we had promised them during the war. Yes, you fought and died for us, on the promise that we would give you your country back. But let us turn the clock back a bit further:

Mother India

England first discovered India and the Far East during Drake’s round-the-world voyage. A few years later, the East India Company was formed in order to trade with the east. Trade by itself is generally a good thing. In retrospect there is little good to be said of the Company. They so far exceeded their brief that they conquered much of modern India and Pakistan, and maintained friendly princes in alliance over the rest. They were only able to do so much because the formerly able Mughal invaders had succumbed to slothful inertia. The Company’s looting of India so far enraged Edmund Burke that he had Warren Hastings – the Governor-General of Bengal – impeached for a multitude of crimes. The trial dragged on for seven years until Hastings was finally acquitted. Burke’s conservative, modernist view of the rights of native civilisations was, alas, too radical for the times. The powder-keg smouldered away for decades until the Indian Mutiny in 1857.

The Mutiny was sparked by a mendacious campaign of lies about greased cartridges. There was no truth in this whatever. The underlying cause was the very fact of British rule. Increasing numbers of Indians wanted the British out. After the Mutiny was suppressed, the days of the East India Company were numbered. With considerable reluctance Britain took over, and Queen Victoria was anointed Empress of India.

But let’s wind the clock back a bit further. Why was the government – as distinct from the corporate freebooters – in India at all? This had nothing whatever to do with an insatiable desire for conquest. Britain was in India to save them from the French. When Wellington (then merely Sir Arthur Wellesley) arrived in India with his brother – the new viceroy – he discovered that India was already being invaded and pillaged by the Maratha Confederacy. He won a great victory at Seringapatam in 1799. At the battle of Assaye (1803) Wellesley faced a hundred thousand Marathas – all armed with guns and cannons, if you please – with six thousand British and Sepoy troops. ‘They won’t stand!’ he remarked, and put the enemy to flight. Unlike his brother Richard, Wellesley had little patience with grand imperialist ideas. Pedantic respect for native rights was the watchword of his regime as governor of Seringapatam and Mysore.

However, respect for native rights only goes so far. One of the statues in Trafalgar Square (see picture) is of Sir Charles Napier. One native custom in particular he suppressed:

I don’t know what you think, but I’m guessing the women of Sind were rather grateful for his intervention. During the siege of Lucknow, every soldier made sure to keep two bullets in reserve for his rifle. One for his designated female ward, and the last for himself. Because the mutineers really did enjoy rape, torture, mutilation and mass murder. Thanks to Havelock’s indefatigable Highlanders (MacGregors, no less! Is Rioghal mo Dhream!) who force-marched through the night to relieve the exhausted garrison, these extremities were not to be invoked after all.

And no, Britain did not cause the great famine in India. Repeat the talking points of the BJP if you must; but this is propaganda, not history. And do bear in mind the company you’re keeping here. Here’s a great example of the rewriting of history. Look up the Mumbai plague of the 1890s on teh interwebs and you will read how brutally insensitive the colonial government was, with their suppression of the Ganesh festival and forced disinfection. What the Raj did was attempt to save lives. Was the worship of Ganesh suppressed, because that deity was represented by a rat (mushika)? Thanks to a bright young officer at the ICO, it was discovered that another face of Ganesh was the elephant. Many locals were persuaded that they should give honour to elephants rather than rats. Whenever you see an elephant statue, remember this.

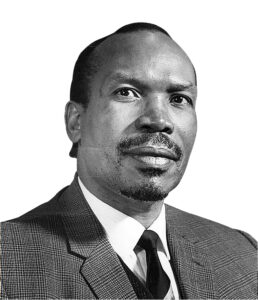

Two unfortunate events blighted the celebrations of 1947. One was Mohammed Jinnah, the warlord of what was to become Pakistan. He threatened war to the knife if his people were to be ruled by Indians. Had the British known he was dying of cancer they would have stared him down. The other problem was that Britain mistrusted the Congress Party, and Nehru in particular. History has justified this view. They wanted to hand the keys of India to Ambedkar:

Everyone agreed that he was the best choice, except for the unfortunate fact that he was a dalit. And the Brahmin caste would never accept an Untouchable to rule over them. So Congress and the Nehru family it was, with some reluctance. Once they quietly rid themselves of the Nehrus, and largely ditched the Permit Raj and some bodgy LSE-inspired economics, India became a superpower. There are many reasons for this. The BJP doesn’t want you to know this, but largely keeping British institutions certainly helped. They will claim that India’s long history of civilisation and tradition of wealth creation was certainly a factor. They are absolutely right to do so.

India is now in charge of world cricket. Beating them in any contest is now the pinnacle of achievement. Do we mind? No, of course we don’t. We feel that the BCCI is too greedy and selfish, and should not be ruling with such an iron fist. But what would you? By and large, their power is exercised with a fair degree of moderation and even-handedness. And their World Cup win in the women’s game has made every woman in India walk taller. Watch India’s women on TV and you will see filled grandstands with families. India has not been notable for female emancipation, historically speaking. This is changing for the better. I expect this would bring a smile to the lips of the worthy Dr Ambedkar.

Being more British has helped the decolonised powers enormously. Those who rejected Britain (Zimbabwe, you’re being judged here) have descended into failed states. Those who embraced British institutions have prospered. Look upon Somalia and Somaliland. Where? you may well ask. The former is a disaster area. The latter is never in the news because they’re doing just fine. It was a British colony, which was later incorporated into the former. By 1991 they’d had enough, and seceded. The government in Mogadishu, such as it was, realised that they had enough problems already and let it go. Anyone who wants to utter race-based nonsense about Somalis can go take a running jump off a short pier. Because some of them are friends of mine. Those who have come to these fatal shores, by and large, have prospered and integrated. They know they have escaped a failed state and are grateful. The difference between a failed state and a working one has nothing whatever to do with race. It’s about making workable institutions.

Allow me to introduce the greatest hero of 20thC Africa. (No, not the one you think.) Sir Seretse Khama was the founding President of Botswana. He loved jazz and went to London clubs, where he met an English typist called Ruth Williams. They fell in love, and he confessed his terrible secret, viz and to whit that he was the Crown Prince of Bechuanaland. Ruth, I hope this doesn’t ruin our nascent relationship. After she had recovered herself, she assured him that it didn’t. They both received a good deal of fairly awful commentary. Mixed marriages weren’t popular in exhausted 1950s Britain. Back home the locals weren’t too keen on her either. But Ruth Khama’s simple goodness won everyone over. In due course, after some argy-bargy with the Colonial Office, Botswana was granted independence. It is also rarely in the news, for the simple reason that Seretse was a political genius. Despite Britain’s mistreatment of him, he kept all their institutions, with the office of the Presidency in place of the monarch. At a time when colonial railways were being vandalised all over Africa, he invited retired railwaymen from England’s Deep North to come and fix everything. He met them on the tarmac, paid all their expenses, and they put everything back on the rails. (No, you won’t read this on the internet. But it was a fact. I have seen TV footage.)

At a time when African dictators were plundering the postcolonial treasury and riding around in luxury limousines, Seretse drove a battered old second-hand utility. He accepted a tiny salary. He was effectively telling his people look. I am Seretse Khama. You know who I am. I don’t need any of this stuff to prove my worth. We are a poor country. We have diamonds and desert. We will not plunge ourselves into hideous debt. (Their net debt, even now, is tiny.) We will be Open For Business. But on our terms. You will not treat us as poor ignorant blecks because we won’t tolerate that. But we will give you stable institutions and enforceable contracts. The rule of law applies here, under an independent legal system which may at times defy the government itself.

Ask anybody thereabouts frustrated by the enduring horror show that is life in Africa, and they will tell you Oh if only we were more like them!

And some of the former British colonies are now learning from them. When there is a picture of this wonderful man in every house on the African continent, you will know that there is hope at long last. If you would learn more about him, and Ruth, watch a movie called United Kingdom. It is an excellent, and mostly accurate account.

A complete refutation exists of the Decolonize Now! mantra. When the Portuguese dictatorship came to an end in 1974, the new government abandoned its colonies to their fate. Angola and Mozambique headed straight into wars of conquest while the world washed its hands of them. Apparently Soviet imperialism is quite all right; because Russia isn’t The Evil West. Both countries are still miserable places. The Portuguese were bad colonial masters, and did not encourage the growth of stable institutions among the local populace.

Timor L’Este fared even worse. Indonesia brazenly invaded them, slaughtered the locals, destroyed whatever infrastructure there was and treated the survivors as serfs. Again, the Indonesians were allowed to get away with it because they weren’t evil Westerners. The brutal occupation continued until Australia took a hand and (with Uncle Sam’s logistic help) decolonized the decolonizers. The American view – privately expressed to the Indonesians – was this:

As often happens on such occasions, the freeing of Timor L’Este had a thawing effect on Indonesia. The military dictatorship gave way to democratic rule. Strange but true.

The phrase ‘hearts and minds’ will be long remembered by those ancient enough to recall the colonial war in Annam and Tonkin. It was a favourite of General Westmoreland: the senior officer in charge of what the USA was pleased to call its peace-keeping mission in South-East Asia. He was excessively fond of quoting it. The Vietnam War, he claimed, was a battle for the hearts and minds of the locals. Westmoreland’s surprising legacy to the US military was not entirely negative. He has gone down in lecture-rooms from Annapolis to the shores of Tripoli as a classic exemplar of How Not To Do It. He wasn’t as incompetent as Admiral Kimmel; but then, a pound of Kraft cheese might have defended Pearl Harbour more effectively than Kimmel.

The phrase was actually devised by Sir Gerald Templer, the last British governor of Malaya. His predecessor Sir Henry Gurney was assassinated by Communist guerillas. It was a fervid epoch, in which insurgents of all colours felt that their time had come. Templer had other ideas. Rather than assuming that terror must be met by counter-terror, he assumed that the root causes of the insurgency must be addressed. After some in-depth questioning of the locals he realized that the desire for independence was not merely Communist propaganda. You want your country back? Very well: you have my word on it, as soon as the insurgency has been crushed. And crush it he duly did. Cheng Ping and his ragtag army were completely outmanoeuvred by Templer; both in the field, and more importantly in the propaganda war. Templer was a master of public relations, and his use of film to isolate the insurgents was both brilliant and effective.

The point was that the Malays believed him. They had nothing to gain by throwing in their lot with the Communists, whose cruelty and violence were extreme even by the exceptionally gruesome standards of the twentieth century. When Templer realized that many villages were cooperating with Cheng purely out of well-merited fear; he withdrew them to camps, burned the villages to the ground, and assisted the locals to rebuild their lives and their properties once the Communists had been routed. His motto might well have been Severity Without Cruelty. He was something of a martinet, feared by friend and foe alike. But he was as good as his word; and once the Communists had been routed, the Malays were given their country back as promised.

Now this wasn’t the last we heard of the Communists. There was a second Emergency which smouldered well into the Eighties. But this was no longer Britain’s concern; and their legacy was positive enough for the Malays to triumph. Britain disapproved of the special privileges the Tunkus insisted on for ethnic Malays at the expense of the Chinese; but this is an imperfect world. You take what you can get, and be grateful things aren’t even worse. Templer’s success in Malaya caused the Americans to hire him as a consultant in the early stages of their own brush with Communism in Vietnam. It lasted mere months. In an icy fury Templer told the Americans: ‘If you will not take my advice then I decline to act for you any further!’

Fashionably-inclined Boomers may well reflect on this calamitously missed opportunity. And no-one seems to remember now that Britain declined to take part in the Vietnam fiasco. Lord Mountbatten was commissioned to write a report on the advisability of helping out our transatlantic colleagues. His verdict was unambiguous. Do not touch this with a boat-hook. Just no. Australia did, regrettably. Sir Robert Menzies, our Prime Minister at the time, had thrown in his lot with the USA. Menzies was a somewhat more skilled diplomat than history recalls, despite the fact that he embarrassed himself several times on the world stage. His view of the English (‘You have to stand up to them, or they’ll walk all over you’) was astute enough, although we wish in retrospect he had been more thorough about it. But he had a terrible blind spot with the USA. We may console ourselves with the reflection that our small expeditionary force was actually successful. It wasn’t our fault that our allies seemed more interested in indiscriminate slaughter. We are remembered in that part of the world with more affection than many would believe.

The postcolonialist protection racket must cease!

Why is it that only England is being asked to give up its treasures? The Louvre is filled with artefacts looted by Napoleon Bonaparte. Ask the French for the return of the Apollo Belvedere and they will laugh in your face. Ask the Venetians to return their looted Byzantine mosaics and no-one will lift a finger. Reparations for slavery? Excuse you? Who abolished the slave trade? Why, that would be Britain. Nobody alive is a slave of the British. That was long ago, and Britain repented. There are, at last count, nearly thirty million slaves in the world now. Their number increases daily. Where is the outcry from self-seeking politicians about this? Colonial war reparations? When Turkey pays Greece for four centuries of slavery, and Armenia for the genocide there; and when Russia pays Ukraine for the Holodomor; when all the world comes to the party and gives back what was taken; come back to us then.

Why is Britain alone singled out? Actually, this is largely a matter of English politeness. Not that they are always civil. They do studied rudeness better than anyone except the French. But instead of indignant repudiation, the English will nod, smile, and say something like Perhaps there is something in that. Let it be known, however unintentionally, that you are open to being blackmailed, and watch the locusts mass on the horizon. The only solution to this campaign of blackmail, bullying and intimidation is this:

The Loyal Revolution in Anguilla

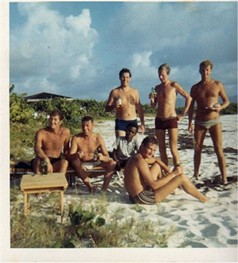

This is a tale all but unknown these days. As part of the Great Decolonization, Harold Wilson – the pipe-smoking Labour PM of the day – had decreed that as part of the breakup of the West Indies, St Kitts was to be united with Nevis. So far this made sense. He then added the tiny island of Anguilla. (I still have somewhere a stamp issued in the name of St.Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla.) But the new state did not persist because Anguilla rebelled. A regiment of Paras was sent to suppress the rising. They disembarked to find the town centre entirely unengulfed in flames. And rather than go around shooting people, the troops took the opportunity to relax. This is a contemporary photo:

‘What the hell is going on here?’ the commander wanted to know. ‘Where’s the fighting?’

‘We don’t like Kittitians. They invaded our island!’

‘Where are they then?’

‘Oh, there’s only one of him. We locked him in the post office. Please take him away. We have nothing in common with them. We only want to live as we have always lived.’

‘So you want to go it alone? All ten thousand of you?’

‘No, we want to remain part of the United Kingdom!’

Eventually they were given what they wanted in 1980. Anguilla was a settlement of Caribbean slaves who’d escaped from indentured labour elsewhere, and took over the island. So far as we know, no attempts were made to recapture them. And they elected to stay with their former masters. This is not how things are supposed to go in postcolonial studies. Yet it is a fact, and a highly inconvenient one for anti-imperialists.

Nobody is even suggesting we turn the clock back to the Empire. But the British Empire (on which the sun never set) was obtained during a number of terrible wars in which Britain’s very survival was at hazard. Having seen off a boxed quadrella of European dictators (Phillip II, Louis XIV, Napoleon and Hitler) Britain sensed that the world was changing, and handed back all their colonies. Some wanted to stay, like Anguilla and Gibraltar. This was permitted, naturally. Others (Canada, Australia and New Zealand) decided to stick with the monarchy, while requesting complete sovereignty otherwise. And this, too, was granted. If you’d like to change this now, I believe you are throwing away a priceless jewel. More on that later.