‘Bertie, please tell me that we didn’t do this?’

It was a hot, muggy day in late August. Rain looked to be imminent, and it couldn’t come too soon. She stared out the window, waiting for her husband to answer. His speech impediment, though still pronounced, was less problematic these days, though the nervous tension which caused it still ate away at him. She would far rather spare his feelings, but some questions could not be passed over. With her back to him, she heard the striking of a match. He was, inevitably, lighting a cigarette. This would give him additional time to answer her question. But he would not lie to her. Of this at least she was certain.

‘You – mean about G-george?’

Still with her back to him, she went on. ‘Yes, dear. George. We didn’t have him killed, did we?’

A long pause, punctuated by several puffs. ‘No, we really didn’t, d-dammit! And yes, we would know about it if we had, but we didn’t. It was just what it looks like. A b-b-b-blasted accident.’

‘Yes, dear, but why did we send him to Iceland, of all places?’

‘To keep the silly b-b-b-bugger out of the way. We sent his idiot brother to the West Indies and we sent Georgie to the bloody N-n-n-north Pole to keep him out of m-m-m-mischief.’

She considered this. It made sense. Better to keep Bertie’s half-witted siblings as far apart from each other as possible. By themselves they were a menace. Together, they might imperil everything, even in exile. But killing off your own family? Indeed not. That simply Isn’t Done. Their hands were guiltless after all. But poor Georgie had always been a danger to shipping. And now he was dead, killed in a plane crash. In the middle of a world war, it seemed somehow stripped of its tragic overtones. She was more truly sad for his bereaved lovers. Her husband’s hand reached gently over her shoulder and laid itself on her breast. She placed her own slim, delicate hand over his and held it there in comfortable silence. And remembered another interview, some years ago, in another room. That had been about Georgie, too. Georgie – though by no means stupid – had the unfortunate gift of making trouble for everybody else, and smiling anxiously like a large dog who has chased a rat into a drawing room and knocked over an entire cabinet of Ming china. He meant well. He had not a malicious bone in his body. This didn’t make it any better at all.

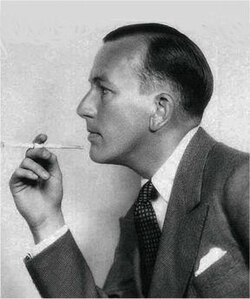

She had been nervous that day. Quite unaccountably so. But there was something terrifyingly self-assured about the young man sitting opposite her. (Young man! He was a year older than she.) She had met him many times, but she couldn’t fathom him at all. She had known so many pretty young men. The doomed aristocratic youth of Waugh’s novels, drinking and fornicating their way into oblivion – she had known them all and sympathized, up to a point. Even though she believed privately that self-destructive behavior of that sort was not merely silly but a sinful waste of a good party. She hadn’t met Waugh, but she could place him accurately enough. At bottom, just another Tractarian zealot beneath the undoubted wit and sympathy. But this one? He sat, composed, with his hands resting on his knees, waiting for her to speak. And for once in her life she did not know what to say. He had greeted her appropriately enough, but she had sensed at once the unearthly sang-froid beneath the warmth, charm and friendliness.

Now he looked at her quizzically. Was he wondering if he should break the silence? It seemed so. ‘I have been rather expecting this,’ he said.

‘You surprise me,’ she answered at once. ‘May I ask why?’

He leaned back, and accepted a cigarette from the silver box on the occasional table at his right. ‘Beauchamp has gone abroad, I gather.’

Beauchamp! Beauchamp was, let it be admitted, a colossally foolish man. After all Bertie’s father had done for him, he thought his eminence made him invulnerable. Bendor, who had married Beauchamp’s sister-in-law, hated him with a savage loathing out of all proportion to the offence. And Georgie’s foolish love for the man’s daughter had put poor Beauchamp in the centre of a gunsight. She looked carefully at her guest and admired his discretion. With a single short sentence he had made it clear that he knew perfectly well why he had been sent for, and was waiting for his cue. He smoked companionably and kept his eyes slightly lowered.

She laid a tabloid newspaper face up on the table between them. It was the Daily Trumpet, renowned even in Fleet Street as the journal which went just that one step further. All the rest would cover a funeral. The Trumpet would cover the autopsy. The banner headlines screamed: DIVORCE SCANDAL Ex-Governor’s Unnatural Acts! They looked at it. They averted their eyes. She reached out her hand, picked it up and threw it into the corner of the room. ‘Very well,’ she said at last. ‘Clearly you know why I have summoned you. And now I must ask you to be candid with me.’

The beautiful head bowed slightly. ‘Madam, if you command it.’

‘May I command you?’

A more decisive nod this time. ‘Indeed you may.’

‘Are you an invert?’

The hazel eyes flicked open and shut for a heartbeat. ‘Yes, madam, that is the case.’

‘For how long have you been having erotic relations with the Duke of Kent?’

He took his time with that question. ‘Eight years,’ he answered briefly.

This was staggering. She had made it her business to find out all about Georgie’s lovers of both sexes. Their name was legion. On the list of Certains, Probables and Maybes, this man was listed merely as Probable. But she knew about the picture. Time to bring that up, perhaps.

‘I am given to understand that you keep a photograph of him on your piano. Is this not somewhat indiscreet?’

Now his lips creased in an amused smile. ‘By no means, madam. He is a very attractive man. I have written a song about him. To be sung by a woman, naturally. But those in my position are granted a certain leeway in the public imagination. They imagine we merely flirt with the idea sentimentally, like a butterfly hovering around a Venus flytrap admiring its outer foliage. So long as discretion is maintained, there is very little risk of exposure.’

‘But not no risk.’

Again the easy smile. How haunting those eyes were! But she already knew what a consummate actor the man was. ‘Madam, if I wished for certainty I would resign my position in society and go and live as a dustman in Chiswick. I doubt I would find it congenial.’

She laughed, suddenly presented with an absurd vision of her guest as Alfred Dolittle. ‘Nevertheless, what assurances do we have of your discretion? There are such things as love letters and photographs?’

That brought his eyebrows down in a flash. ‘Madam, there are no letters and there are no photographs,’ he said with asperity. ‘Not on either side. Except for the picture on my piano. As for my future discretion, madam, allow me to reassure you that I am an Englishman and will do my duty by my King and Country.’

Well, there was a speech. Bright Young Thing he may be, but there was a steely resolve which she found enchanting. ‘Beauchamp is ruined because he thought himself invulnerable,’ she continued. ‘He was shockingly indiscreet, and alas, he must pay the price.’ She sighed. ‘Neither the high nor the humble can escape Nemesis. Our society is intolerant of inverts. I wish it were not so, but he cannot now return to England. And poor little Maimie will never wed her fairy tale prince. Do you know her?’ she asked.

Her guest lit another cigarette. ‘I do. Poor Maimie. And poor Bendor. What a dreary little fellow. It must be frightful to be the richest man in England and have no higher ambition than to break butterflies on wheels. I am sorry for all Beauchamp’s girls, but I daresay that fellow Waugh will look after them.’ He pursed his thin lips and rolled his eyes, ever so slightly.

‘You do not admire Waugh? You two have much in common.’

‘I do not. He has considerable gifts. But he is the only man I know who goes courting with a butterfly net and seeks out entire families for his affections.’

She laughed again. ‘Very well put. So you do not wish to pay court to all of my family?’

‘No, madam. Just the one. Even he is more than I deserve.’

Another silence. ‘Speaking of families, what can you tell me of your own? I gather you have rather a large tribe of them living in your house? I am given to understand that they are not notable for their discretion.’

Again the eye-roll, more pronounced this time. She wondered if she had gone too far with this admirable man. But the question had to be asked. ‘Madam, my family is something of a trial. I have gathered them all under one roof so they can bicker and complain and vex each other as much as they please and not annoy anybody else. My own quarters are separate, and I have as little to do with them as I possibly can. And that, madam, is my own form of noblesse oblige. Since I am wealthy but parvenu, I support the otherwise insupportable.’

She laughed long and merrily. ‘Very well. I will not threaten you with the fate of Beauchamp. I have decided to trust you. Do not let me be mistaken in you. And I wish that my brother-in-law would be as discreet as I believe you will continue to be. But that may well be too much to ask.’ She rose, extending her gloved hand. ‘Thank you for your time, and candour, Mr Coward. I hope to see you again. You have amused me, and I value this greatly.’

Her guest rose, lithe and quick as a cat. ‘Please, call me Noël.’ He took the gloved fingers and kissed them lightly.

‘Noël it shall be.’ She inclined her head graciously. ‘And you may call me – Ma’am.’

************************************

Her husband left the room, and she stared out the window at the grey, dusty road outside. Noël had been as good as his word. Bertie had blustered somewhat, but he had come around. She and Noël had spent many happy evenings together and he had said not one single word to anybody about their doings. Perhaps Bertie realized that leaving his wife alone with a man who preferred the company of gentlemen was far safer than others who might well be smitten with her undeniable charms. She was a famous beauty, after all. Now she sat alone smoking, until a momentary noise behind her gave notice her husband had returned.

‘Bertie? Who is taking care of the funeral?’

‘I am.’ He sat next to her and lit another cigarette. They held hands for a moment and stared out the window. ‘It’s to be in three days. I suppose we must invite all the usual gang.’

‘It can scarcely be avoided,’ she responded. ‘All those dreadful politicians. But Winnie will be there. You always enjoy his company. Please tell me we don’t have to invite Davie and that awful woman. I shall be very cross if we do.’

‘I don’t see how it can be avoided,’ Bertie answered, withdrawing his hand.

‘Well, in that case, I’m bringing Noël. If I have to put up with her then I want him there with me. It’s no use you saying you’ll protect me from her. You’ll be busy. You cannot refuse me that, Bertie dear.’

Bertie took his face between his hands and kissed her on the forehead. ‘You love him, don’t you?’ he asked gently, without a trace of stammer. ‘May I ask why?’

She took his hands and kissed them, one after the other. ‘Bertie, listen to me. You don’t remember, do you? Your heart was always in the Navy. That was what you were born for, wasn’t it? Until this dreadful job turned up and you had to do that instead. I was a flapper, a Bright Young Thing. Everyone remembers us as cheerful, heartless, brittle revellers. But we knew what we were up against. A third of our young men had been slaughtered in the War. Many of us would never be married. We could sit at home and mope, or go out to parties and have fun.’

She paused, remembering the golden summers of her youth. ‘It was wonderful, but it was sad. That wretched man Waugh had us down pat, Bertie. Doomed youths and maidens, one and all. We would perform our danse macabre and go home to the certainty of middle age and decay. And then Noël came along. A little younger than the others: too young to have fought. Humble background, just like Waugh. But he was different: gay, droll, and amusing, and he liked us. And when times grew hard, he burned brighter. He made new songs, new plays, and new jokes. He gave us the heart of comedy with all that dreary Oxford aestheticism shaken out of it. He made us all feel young again, Bertie. He loves his country every bit as much as you do. Now you tell me that the Secret Service have taken him off the books because of bloody George. I’m not happy about this, Bertie. If we do win this bloody war then part of it will be because of him.’

Bertie cast her an anguished look. ‘Well, that’s as m-m-m-maybe. But –‘

He lit another cigarette, smoked it furiously and threw it angrily into a fireplace. ‘Well, he’s lied to you, Elizabeth. He told you there were no letters. Apparently there are lots of them.’

Her mouth opened in astonishment. ‘What? Where are they?’

‘The bloody B-b-b-b-beaver’s got them. Letters from Georgie to your friend Noël.’

She sat for a long moment, wrapping her scarf around and around in her fingers. ‘None from him to Georgie?’ Bertie shook his head and slumped backwards in his chair with his head in his hands. ‘Well, he could hardly prevent Georgie writing to him, could he? And he’s kept the letters at home, I suppose? Locked away for safekeeping until the Beaver’s bully-boys broke into his house and found them?’

Bertie nodded. ‘All right, as you say. But he’s out of action. They say it’s too big a risk and I agree.’ He threw up his hands angrily. ‘If my father were still alive he’d say they should all just shoot themselves and save us all a great deal of bother.’

‘Yes, Bertie, I can hear him saying it. It’s just the sort of thing he would say. But that doesn’t help us. We can’t help how we’re made, Bertie. And consider: aren’t you better off with a devoted admirer who is no threat whatever to my virtue?’

Bertie smiled and took her hand. ‘Yes, dear, you’re right, of course. I don’t mind you seeing him when you want to. And the fellow’s dashed amusing, as you say.’ His face clouded momentarily. ‘Speaking of Bright Young Things, did we ever do anything for those poor Lygon girls? Beauchamp’s daughters, you know. Can’t very well ask them to the funeral, can we? Are we doing anything to help them out?’

‘Yes, Bertie,’ she answered in an emollient voice. ‘Don’t you remember? We’re keeping Madresfield free in case we need to send our daughters there for safe-keeping. Which means their house doesn’t get taken over by the Army and turned into billets for the drunken soldiery.’

He frowned. ‘Well, that’s something, I suppose. Nice girls, too. Very f-f-free-spirited.’ He looked at his fob-watch and frowned again. ‘Sorry, dear. Must go. Affairs of state and all that. Talk to me about this later, will you?’

And with that, her husband was gone. Would the Beaver ever use the letters for his own advantage? she wondered momentarily. She shook her head. Not a chance. In his own repellent way, the Beaver was a patriot too. Even though he had a colossal hide, making such a fuss about Beauchamp’s pretty boys. And Bendor. His Grace the Duke of Westminster was an unrepentant seducer of underage girls! But that was apparently all right, of course. She ground her teeth for a moment and relented. The letters were safe with the Beaver. Absurd, really. We lock up our young men together at school and Varsity and wring our hands in horror when they turn to each other. Unutterably foolish. Perhaps some day we might stop doing this. She stared out the window for a long time, watching guardsmen marching up and down outside her front gate. If she didn’t get her way over the funeral, she would make it up to Noël for as long as he lived. She could do that, surely? And if not, what on earth was the point of being Queen of England?

****************************************

Georgie was farewelled with as much pomp and ceremony as was deemed fitting in time of war. And afterwards Noël was smuggled into the Palace by the omnipresent plain-clothes gentlemen whose eyes were everywhere, who missed nothing, and who presence was resolutely ignored by the uniformed soldiery. Tea was served, with cucumber sandwiches, and they exchanged glances.

‘Noël, dear, you were outrageous as always. Please don’t flirt with the Horse Guards. Or at least not so brazenly.’

He blinked at her, folded his hands in his lap and said in his best schoolboy voice: ‘I’m very sorry, ma’am. I won’t do it again.’

The royal upper lip trembled. ‘You will, you know. And you were awfully rude to both Beaver and Bendor. Especially Bendor. Your way of saying “AH, how DO you do, Your Grace?” was positively scandalous.’

‘His Grace the Duke of Westminster is an infernal bloody swine, Your Majesty. With all due respect to his noble rank, of course.’

She laughed. She really couldn’t help herself. Bendor was Westminster’s nickname because he was insufferably proud of his heraldic blazon, along with everything else to do with his rank and position. Bend d’or indeed. ‘Very well, Noël dear. But you will not provoke Lord Beaverbrook again. Apart from anything else, he really could ruin you. He wields enormous power in Our government, and I am afraid We really can’t do without him. Do you understand?’

‘Yes, ma’am. As you command. And I really will be more careful with him. It’s just so bloody annoying. In addition to keeping up everybody’s morale with my songs and plays, I have served my country well in – the more delicate matters entrusted to me. I have not let my country down, ma’am. And because of the Beaver I’m not allowed to spy any more. It makes me so angry.’

It was very discreet of Noël not to mention that Beaverbrook’s position of Guardian of Morals was dubious in the extreme. Both of them knew of his long-standing affair with Lady Sibell Lygon. Of all the brass-fronted cheek of the man! She leaned over and patted his arm gently with her gloved hand. ‘I am so sorry, Noël. But it can’t be helped.’

She leaned back in her chair and waved for more tea. Gordon wafted invisibly away. As an invert himself, Gordon’s discretion was absolutely assured. And his presence did away with the need for a lady-in-waiting. Sometimes they could be so tiresome. Gordon was also six feet seven inches tall and had boxed for Cambridge, and his presence in private Royal interviews had assuaged the panic-stricken equerries in charge of security.

‘As far as the Duke of Westminster is concerned, however, after the way he hounded poor Beauchamp out of the country, you may be as rude as you wish. With Our blessing.’

‘Thank you, ma’am.’ Gordon reappeared with more tea and a silver tray of cakes, and melted away into the shadows.

‘Noël, you are of course correct. It is absurd that you and your friends are treated so badly. Is there anything We can do to improve the lot of – of gentlemen who prefer gentlemen?’

He looked at her with tears in his eyes. ‘No more than you do already, ma’am. The time when those wretched laws will be repealed is not yet come. It will, some time later this century. But not for a long while yet. Your friendship says a great deal, ma’am. Not just to me. To dear Beverly, and all the other gentlemen whose company you favour. Naturally it is not widely known; but it is enough to give Beaver and Bendor and the rest of the bigots pause for thought. We know that if we are arraigned, then You cannot save us. But if they proceed, they must know that they offend the Queen’s Majesty. That alone is priceless, ma’am. And now, how may I serve You?’ He glanced across the room at the Steinway grand.

She smiled. ‘I would not have you sing for your supper, my dear friend. But – perhaps you would like to play – that song? In memory of one you loved so long?’

He rose slowly to his feet. ‘I do not think my voice will hold up, ma’am. So if I may be excused the vocal part, I will play Mad About The Boy for You, with heartfelt pleasure.’

He sat himself down at the keyboard and began to play. She watched his lips forming the words, but he did not sing and she understood why. He really had not loved Georgie for his title. This was true love. A pity Georgie had been so indiscriminate in his affections. He played the final chord, looked expectantly at her, and began to play Mad Dogs and Englishmen.

She clapped her hands and began to sing along. From his hidden alcove, Gordon watched them. And he smiled also.

© David Greagg 2016