It’s not what I would have chosen to do right now. But here we bloody are, doing the same old grim times. So we may as well get to know them better. Unconvinced? Consider the following:

- Worsening climate

- Deep pessimism about the future

- Emotional turmoil and angry voices shouting each other down

- Sanguinary civil wars and invasions

- Raw emotion trying to pass itself off as reason

- Rampant republicanism

- Ethnic hatred, bigotry and intolerance of divergent opinions

- Rise of the Puritans and Theocracy

- Public vandalism and wrecking of graven images

And please: this is not a merely a Western-centric view. Rest of the Known World? In China, the inward-looking and civilized Ming dynasty was overthrown by the Manchus. Largely because the latter had fire-arms and were prepared to use them. The Manchus were an unlovable lot. It was they who introduced opium, tobacco, foot-binding for women and pigtails for men. The Ottomans decided to conquer Europe and got as far as the gates of Vienna. Again. They were urged on by the endlessly treacherous Louis XIV, whose Satanic bargain with the Sultan was that they should divide Europe between them. Thanks to the energetic intervention of the Pope and Jan Sobięski’s Polish cavalry the Ottomans were thwarted, and decided to doze off into a narcotic and slothful decline. Only in India was there continuing prosperity under the energetic Mughals. Even there, the latter stages of the century saw weak leadership precipitate a long-term descent into chaos.

Europe was devastated. Spain went into a terminal decline, caused by the Curse of Silver and weak theocratic leadership. France ossified into a similar theocratic slumber, and drifted towards its inevitable catastrophe. Germany almost ceased to exist during the Thirty Years War. The Treaty of Westphalia took eleven years to be ratified. We suspect that had they left it much longer there may not have been anyone left alive to sign it.

Britain was more fortunate, though it did not escape a catastrophe of its own. The great debate hereabouts was not, as on the Continent, Protestant vs Catholic. At least we British were spared that hideous nightmare. In the long struggle between Crown and Parliament both sides were nominally Protestant. The great schism was between Erastianism and Arminianism:

What on earth are modern readers to make of this? Don’t feel too superior. Future generations (should there be any) will doubtless find the contending ideologies of the early 21st century equally baffling. But a wicked strain of Erastianism still poisons the waters even today. The urge to punish thought crimes comes from this particularly repellent Swiss theologian. The Roundheads (Right But Repulsive) were Erastians to a man. The Cavaliers (Wrong But Wromantic) were Arminians. And yet. None of this would have caused the Civil War.

What began the conflict was Charles I’s delusional belief in the Divine Right of Kings. Buchan’s conclusion concerning Charles is undeniable. The man never grew up. Had he been wholly honest, or wholly rogue, he could have kept his head. Charles’ delusional faults are obvious enough to anyone. They were apparent to everyone even in his own day. Yet he had many virtues. As narrated elsewhere he cared for all his subjects, especially the poor and the lowly. And the Irish. His much-reviled Star Chamber was not the instrument of tyranny it has been portrayed as. Rather it was a means of chastisement for the over-mighty who could not be punished by normal means. Yet Charles refused even to consider the idea that absolute monarchy was no longer possible in England. Elizabeth got away with it because she was a genius, and greatly loved. Charles had not enough common sense to come in out of the rain. He refused to believe that the world had changed. And the rising middle class in England had got Religion:

The House of Commons was largely Puritan in flavour. They would not allow Charles to raise money except on their own terms. So Charles prorogued Parliament in 1629 and tried to rule on his own. It was unlawful, naturally. Yet he got away with it for eight years, until a gang of Moroccan pirates occupied Lundy in the Bristol Channel, raised the Ottoman flag, and began slave-taking. An entire Irish village was sold into captivity. This was too much for Charles, who loved his Irish subjects as few sovereigns have ever done. So he levied a new tax, called Ship Money. The idea that the Midlands should have to pay for the navy was too much for the emergent middle-class. The rebels, led by John Hampden, refused.

Matters went from bad to worse. Charles lost his head figuratively, and in the end literally. The English Civil War was largely fought by armies little used to war, save for a cadre of veterans from the German wars. In Germany, wholesale slaughter and mass starvation were the rule. In England it was very different. This is from a letter written by Sir William Waller (Roundhead) to his friend Sir Ralph Hopton (Cavalier):

Many Cavaliers were under no illusions as to their King’s character and duplicity. At the first battle of Edgehill, Sir Edmund Verney carried Charles’ standard.

Despite his advanced age (51), he killed thirty-one Roundheads. All that was found of him afterwards was his hand, still clutching the royal banner.

Despite his advanced age (51), he killed thirty-one Roundheads. All that was found of him afterwards was his hand, still clutching the royal banner.

The Civil War was fought largely by men of honour on both sides. Both sides did their best to lose it. Staff-work was virtually non-existent. Charles insisted on being the supreme commander, and crippled his armies by insisting on garrisoning towns and cities everywhere. The Parliamentary armies wavered and dithered. But a new force was arising in East Anglia: ever the heartland of Puritan sentiment.

Oliver Cromwell is not easy for modern folk to comprehend. Hero or monster? The best that can be said of him is that he was a large helping of both. What is absolutely true is that no more reluctant tyrant nor regicide ever walked the earth. A remarkable quote of his runs as follows: ‘No one rises so high as he who knows not whither he is going.’ He had no idea where he was going. And that was the beginning and end of all his troubles. In 1648 his son-in-law Henry Ireton drew up a new Constitution for England. It was a statesmanlike document, prefiguring the eventual 1688 settlement. The defeated Charles could keep his crown, and some royal prerogatives. But Parliament would be supreme in most matters. A Constitutional Monarchy in fact, such as we now enjoy.

Alas, Charles would have none of it. He plotted and prevaricated to the very end. Buchan’s observation on Ireton: ‘There is no more passionate revolutionary than a disappointed moderate.’ And for Cromwell there was nothing for it but to cut off the King’s head, crown and all. It was a crime which was to dog Cromwell for the rest of his life. He massacred the Irish. He put down the Scots with contrasting mercy and forbearance. He suppressed royalist risings. His New Model Army was the military wonder of the age. Yet his regime in England was a calamity. Having destroyed the monarchy, he watched in horror as the rampant Puritans raped, murdered and plundered with impunity. When he had put down all military opposition, he denounced what was left of the Rump Parliament and dissolved it. Thereafter he ruled as a tyrant.

New pretend Parliaments were called, but without popular suffrage. The immovable obstacle to his Protectorate was the awkward fact that one tenth of the country (the army) ruled over the rest, who loathed them. Oliver knew that he could not afford to call elections for a new Parliament. His adherents had no chance whatever of winning. His anguished cry to Parliament in 1658 is piquant: ‘You drew me here to accept the place I now stand in. There is ne’er a man within these walls that can say, sir, you sought it; nay, not a man nor woman treading upon English ground. I had rather have been a shepherd sitting under a tree and tending my flock.’

Most of England cordially detested him. He was very fortunate not to have been assassinated. But in his corner he had John Thurloe, the best spymaster England ever had. He out-Walsinghamed Walsingham. This humble Essex lawyer gathered in all the threads of sedition and quietly extinguished them. Upon Cromwell’s death, his son Richard was briefly installed as Lord Protector. But Tumbledown Dick had no interest in trying to govern the ungovernable. He retired into private life, and General Monck had had enough. Let us bring back the young king and offer him the crown. Republics don’t work in England. All through the direful Interregnum, the ghost of Charles Stuart, King and Martyr, had haunted England. His trial had been a travesty. The charge against him was, in effect, that he had been found guilty of being defeated in a war against himself. And when he realised that death was inevitable, the better part of his nature rose to the occasion. On January 30th, 1649, medieval England was for a time reborn. The horrified onlookers at Charles’ beheading realised that a monstrous crime had been committed in their name. Charles’ courage and dignity were long remembered, rather than his insane duplicity. And the young king returned in triumph to his father’s throne.

John Wilmot, Lord Rochester, pinned these words to Charles’ bedroom door. Charles’ response tells you a great deal about the Merry Monarch:

This tells you a lot about the Merry Monarch. The best extant depiction of him is in Shaw’s play In Good King Charles’ Golden Days. It is rarely performed. Do read it. What Charles’ reign was about was the rebirth of sanity in a crazy world. He was the most consummate diplomat of his day. He was brought back by the Roundhead generals to appease the populace, and to be a figurehead king. He ended his reign as an all but absolute monarch. How did he contrive this? He dissolved Parliament, and governed through a lavish pension he received from that complete wally Louis XIV, to whom he had promised that he would declare himself a Catholic as soon as he was able to get away with it. He kept his promise on his deathbed. Louis sent Louise de Kerouaille to seduce Charles, who was a notorious womaniser. On meeting her objective Louise was bowled over by the King’s charm, and turned double-agent.

Compare and contrast. At a time when Louis was building Versailles as a prison for his aristocracy, Charles laboured to bring sanity back to a kingdom in sore need of it. You hate Catholics, and wish to pass Acts of Parliament to destroy them? Very well. I will sign them. For now. He made several attempts to bring in Declarations of Indulgence. His Parliaments rejected them. The Whigs eventually overreached themselves by murdering Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey – a notable Protestant magistrate – and blaming it on the Catholics. There was said to be a Popish Plot to murder the King and instal his Catholic brother James The Idiot in his place. Charles didn’t believe a word of it, but was obliged to watch on in horror as Titus Oates’ witch-hunt claimed several innocent victims. Eventually Charles got his way, and Oates was exposed as a shameless liar. Charles could have had him executed, but opted instead to have him pilloried, and watched with amusement as the mob turned on their former darling.

And Charles founded the Royal Society. In future, science, logic and reason would receive royal patronage. It was the age of Newton:

Newton was an odd fellow. But his eccentric opinions were always grounded in reason. The perihelion of Mercury wasn’t where it should be, and he took note of the fact. (We now know this is due to relativistic bending of light around the sun.) He also saved England from bankruptcy when he was made Master of the Royal Mint. The Royal Society Fellows argued constantly. But it was generally about science rather than dogma.

All this was down to Charles’ patronage. He was loved, despite England’s superstitious dread of Catholicism. Wouldn’t it be nice if everyone was nice? was the watchword of his reign. And slowly but surely, the simmering lunacy of the seventeenth century ended – in England at least – in a steady growth of tolerance. When his brother succeeded him, in three short years he managed to destroy all the accumulated goodwill he had inherited. But England’s response was to tip him off his throne, and invite William of Orange – who was married to Mary Stuart – to rule instead. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 was an extraordinary occurrence. In England (though not, unfortunately, in Ireland or Scotland) there was remarkably little violence. William accepted the Constitutional Monarchy he was offered, and the modern world was born.

Even in the extreme ferment of Puritanism England did things differently. During the Interregnum, a number of idiosyncratic sects formed which were quite unlike anything the rest of Europe had devised. The Levellers – basically ur-Communists – were a plague and a nuisance to the Lord Protector. But one branch of them, led by Winstanley, gained a certain notoriety as The Diggers. Inspired by the Book of Samuel and the Acts of the Apostles, they took over a few parcels of land and cultivated them for the common good. Cromwell summoned Winstanley, decided that here was a godly man no threat to anyone, and ordered that they not be molested. The Digger movement petered out, but other mystics followed. Like John Bunyan, whose Pilgrim’s Progress is one of the great stories of humankind.

For Bunyan, the world was a stark and terrifying place. Yet with faith and courage, Christians may attain the Delectable Mountains.

And the Society of Friends was formed during Charles’ reign. Charles met George Fox and was impressed by him; and did his best to ignore, or at least moderate, Fox’s fervent anti-clericalism. The sect founded by Fox was something else. Fox began as part of a more general grouping known as The Seekers. Some of them fought for Cromwell. Gradually they became disillusioned with fighting, feeling that it solved nothing, and was contrary to Jesus’ teachings. And they fell out with the Puritans over the latter’s persecution of them. When the Puritan refugees founded Massachusetts, being a Quaker was made a capital crime.

Friends refused even to enter churches, or steeple houses as he called them. They refused to recognize worldly spiritual authority at all. Fox’s meetings were simple affairs, held often in the open fields or at markets. Prolonged silences were not uncommon, as they and their colleagues pondered the glory of God. Outside his meetings Fox was anything but silent, and frequently denounced anybody and everybody. He refused to pay tithes. He would not remove his hat in court. He protested against war, cruelty and savage punishments. Often imprisoned and threatened with execution, he continued to preach until his death. His legacy lives on in the Society of Friends, or Quakers as they were called by a hostile judge. Modern-day Quakers do not reject this label, although they are more comfortable with Friend.

Like many revolutionaries, Fox needed a helping hand. Margaret Fell is now recognized as the co-founder of the Society of Friends. There is reason to assume she was the brains and heart of the movement. She certainly provided the money; and after her own husband died she married Fox. He gave her a bright crimson shawl as a wedding gift. Plain dress for Friends did not necessarily mean dull colours and styles. For those who thought thus, Margaret commented: ‘This is a poor, silly Gospel.’

At the time, women’s contributions went unnoticed by the world at large. (The amount that this has changed in our own day is still disputed.) Among Friends themselves, men and women were regarded as equal from the beginning. This was a remarkably modernist view. It found no favour with their fellow Protestants at all. Friends were persecuted relentlessly until Charles II persuaded his Parliament to pass the Toleration Act. Charles had suffered torments in his youth from the crazy fanatics of the Kirk; and it doubtless brought a grim smile to his saturnine features to have their self-assumed right to persecute others suppressed. And William Penn was a friend of the King. One day when they met, Penn refused to take his hat off. This was the royal response:

Sooner than make a fuss, Charles removed his own hat. It is certainly true that an entirely pacifist religion has an intractable problem with maintaining its own independence unaided. This charge has less force than is sometimes attributed it to it. Penn was a notable swordsman. Many a time he was challenged to a duel by enraged men of property. Trusting in his superior skills he would always accept, and easily disarmed his adversaries. Those who go about doing good and fear nothing but God can be a powerful force in the world. When they inspire the mighty by their dauntless example, the results can be spectacular. The Quaker Thomas Clarkson was the driving force behind the abolition of the slave trade. But it is equally true that nothing would have happened without William Wilberforce MP, and his increasing company of friends in both Houses of Parliament. I need not recapitulate the story, as it is retold (with only minor inaccuracies) in the film Amazing Grace.

Even with the Act of Toleration Friends could not take government positions, nor attend universities, since they refused to swear oaths. ‘Swear not by heaven, which is God’s throne, nor by the earth, which is his footstool, but let your Yea be Yea, and your Nay be Nay’. And so they went into business. And it is well indeed for England that they did. During the 18th century, it was a nation of drunks. It is very difficult for modern eyes to credit just how comprehensively sozzled they were. One reads of dinner parties in which gentlemen were expected to consume four bottles of wine. Each. Drinking alcohol was certainly better than contracting fatal illnesses from polluted water; but really? Four bottles? Among the peasant and artisan classes, gin was drunk by the pint. The Society of Friends was scandalized. What did they do? Agitate for Temperance? They did. But as the 18th century lurched on faltering feet into the 19th, the Friends decided to do something practical about it.

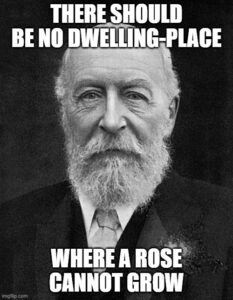

George Cadbury came of a long-standing Quaker family. His father John had run a successful tea, coffee and cocoa shop. All these were hot drinks, guaranteed to kill off cholera and other deadly microbes; and less likely to have their imbibers falling down drains and getting into fights with lamp-posts. Later he converted to chocolate, which was solely for drinking in those days. George and his brother Richard then imported a Dutch chocolate press. They did not invent the chocolate bar. What they did with it was something else. They used only quality ingredients (no brick-dust or dead rodents here) and soon their chocolate bars became the market leader. But the brothers had not even begun their crusade. Using their new-found wealth they retreated from the horrors of the Black Country and made a model factory by the river Bourn. In the verdant West Midland countryside they housed their workers in a model village (called Bournville). All the while coining money hand over fist.

The brothers also pressed ahead with other agitations. The founding of the RSPCA and the institution of the old age pension can be ascribed to their zeal for improving the world. On Richard’s death in 1899, George converted the Bournville estate into a family trust. He left libraries, parks and open land to the City of Birmingham, and went to his eternal reward covered in glory. Please note that the Cadburys did not even attempt to prohibit alcohol. Their view was that happy, contented workers who lived in clean, comfortable houses would not wish to drink themselves into paralytic oblivion.

The chocolate revolution was by no means confined to the Cadburys. Joseph Rowntree (another Friend) was nearly as successful; and only his dismissal of milk chocolate as a passing fad arguably prevented him becoming a market leader. (Parenthetically, Rowntree’s family Trust still provides funds for Quaker and other worthy causes to this day.) The first chocolate company was founded by another Quaker, Joseph Fry. His company was not as successful as Cadbury’s, possibly owing to a failure on his part to implement his beliefs in the workplace. Married women were not allowed in his factory. And conditions there were by no means as pleasant. Yet the family name is remembered with honour largely because of Elizabeth Fry, who visited the imprisoned and campaigned relentlessly for reform of the world’s jails and justice system. Her work bore astonishing fruit; and her crusade for mercy to be admixed with justice was one of the wonders of the 19th century, not only in Britain but across the Continent. The Quakers did indeed come to do good. But they certainly did well for themselves in the process. One Friend even invented the process for bottling beer.

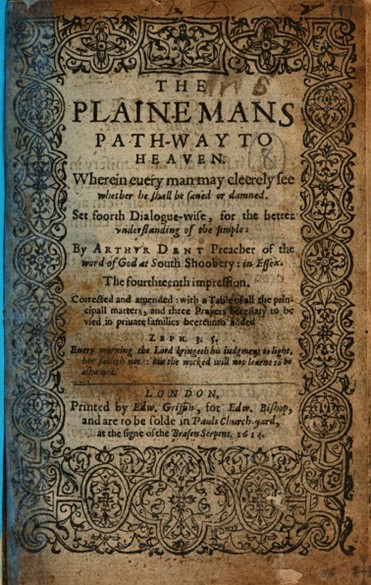

I could go on about this glorious company, but that is enough for now. Puritanism is not necessarily an evil. Sometimes it can transmute into something altogether wonderful. And please note that the best of this century of agitation was born and flourished in England. If you must relive that direful century, try this out; and leave the joyless bedrock of Puritanism behind you.