The Mythos of Scotland

The proper name for this rugged and beautiful land is Alba (pronounced Alapa). Even though it’s Latin (= white), but somehow the name stuck. You can call it Caledonia instead if you like. Scotland’s central problem isn’t that, like England, it contains multitudes. (Like Walt Whitman). Alba proper consists of Angles (Lothian and the Borders); Gallgaels and Brythonic Welsh (Strathclyde and Galloway); Pictland (basically north of Glasgow, but mostly the Grampians); Dalriada (Argyll and points north); and Suthreysklond (all the Norse lands: Orkney and Shetland especially, but also most of the Isles). The English and Scots have learned to cope with being multitudinous. But Scotland being a small country has meant that the Big Time is generally south of the Border. So most of the best brains there have concentrated on impressing the English. Did it work? In some respects it worked rather too well.

Scotland has both suffered and benefited from Tartan Culture. If you visit the Clan Donald Centre on Skye you will discover for yourself all the horrors of Tartan Kitsch. But, as the locals told me: ‘The puir man needs the money.’ What English folks think of their northern neighbour has rarely shaken hands with reality. Victorian tourists expecting well-tamed picturesque hunting lodges and kilts apparently turned back in horror at the borders of Sutherland. Here is Cul Beag (= Little Back). Raised on the novels of John Buchan, I decided to climb a mountain in Sutherland and picked this one. It is rarely climbed and I can see why. But there it is. Scotland proper is not for the faint of heart.

Eilean Siar (the Western Isles) is the heartland of Alba proper. Gàidhlig in various dialects is still spoken there, and this is very much as it should be. The central mythmaker of what people imagine to be Scotland was bloody awful Sir Walter Scott. He had no idea what real Highlanders were like; but he just loved the whole concept. Hence Rob Roy, Waverley, the Heart of Midlothian and so forth. As with his mock-medieval romances like Ivanhoe, he caused all Europe to fall in love with his fantasies. Scott’s memorial in Edinburgh is truly monumental:

One person whose imagination he captured was Albert the Prince Consort. Albert has been poorly served by his uniquely horrible monument in Hyde Park, and the concert hall that bears his name, which looks like a gigantic petrified Sontaran. (Good taste was not a Victorian virtue.) But Albert was a truly great man behind that ridiculous moustache and awkward Teutonic manner. He was a wonderfully kind, loving husband to the terrified teenage girl to whom they married him off. He held the hand of the Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel to such good effect that the Whig Opposition were enraged by it. Albert knew that the safety of the realm depended on Peel, and gave him all the help he needed. He founded many charities. And he brought Christmas trees to England.

And Albert fell in love with Caledonia. That it wasn’t the real Scotland truly doesn’t matter. What it gave the Scots was a place of undisputed honour in the United Kingdom. Had his wife understood more, She would not have encouraged George Granville Leveson-Gower, whose shameful role in the Highland Clearances is now a matter of well-merited public infamy:

This is his monument, erected by public subscription. The statue has been extensively vandalized. Many locals think it should stand where it is, as a reminder that those who do evil to others and say It’s All For Your Own Good are still with us to this day. I really can empathise with those who would like it torn down, crushed into fragments and turned into a public urinal in Golspie, or Lairg, or Dornoch. But that’s all too redolent of the 17th century Puritans. Leave it where it is, with a suitable plaque inscribed with the words Bliadhna nan Caorach. This would in turn encourage visitors to look up what it means. (= Year of the Sheep) All I will say here about the Clearances is that at least he was the only Englishman involved. It was a shameful epoch, but it was a betrayal of Alba by their own chiefs. The only chieftains who did their duty were Lord MacDonald of Sleat and Lord Macleod of Dunvegan. Which is why Skye is still… different. Eilean a’Cheo is a magical land, for so many reasons.

And yet amid the horrors of the Clearances something rare and miraculous happened. The entire Long Isle (Lewis with Harris) was sold off to Sir James Matheson, who assembled the locals in Stornoway:

When he took a boat to Harris they showed him their tweed. Is this any use? they asked him in Tarbert. Look, I can sell this all over the world. Keep it up! The Long Isle is still there, and still speaking Gàidhlig. This sign is in Stornaway:

(Reading from top to bottom, it says Art Gallery, Castle, City Library, Nicholson Sports Centre, Post Office, Bus and Ferry, Police Station, Tourist Office.)

Elsewhere it was grimmer. Barra was cleared out. Much later, the wildly improbable Sir Compton Mackenzie, novelist and spymaster, bought some of it and summoned Clan MacNeil from far and wide to come home. He was an absurd caricature in some respects; but is still remembered kindly there, as he should be. He wore the kilt and spoke bad Gàidhlig. He also rebuilt St Finian’s church, and made himself a ridiculous U-shaped house, not in Baigh a’Chaisteal so he could play at being a laird, but on the isthmus so he could keep an eye out for unwelcome intruders by sea and air. If you visit, do pay your respects to his tombstone in Eoligarry churchyard. It is plain and unadorned, without even his KCMG. This boastful self-aggrandiser had a pious humility which emerged at odd times. His novel Whisky Galore is his valentine to his beloved adopted homeland.

On Skye, the oppressed crofters rioted, and drew a House of Commons committee to inquire what on earth was wrong with them, and why they weren’t playing bagpipes and wearing kilts and generally being picturesque? Where do we bloody start? growled the locals. The result was the Crofters’ Act of 1886, which gave them nearly everything they asked for. Much of this unexpected kindness you can chalk up to Prince Albert, who made Scotland fashionable. (Just don’t wear his tartan. It’s truly horrible.) No, the English still don’t understand the Scots, by and large. But they like them a great deal nonetheless. Here’s a brief summary of Scottish history, in case you don’t know it.

We know remarkably little about the Picts, who – while not the original inhabitants – qualify as reasonably indigenous. Tacitus was a Roman author who loved his noble savages. He wrote a thrilling account of the battle of Mons Graupius, in which the Romans were victorious. The famous quote: ‘They make a desert and call it peace’ is from Tacitus: (although there is every reason to think Tacitus was romancing)

The Romans could not afford to conquer Scotland. Eventually they built a couple of walls to discourage southbound holiday-makers and left the Deep North alone. Like the English later on, they realised that there was no point in trying to annex a wild and rugged land that had too little in it that they wanted.

It was once hoped that the Ogham inscriptions in Scotland might turn out to be Pictish, but every single one is in fact written in Old Norse. I know this because the definitive book on this topic was written by Richard Cox, formerly of the University of Aberdeen. I have read it – I had to go to Aberdeen to find a copy – and I am convinced. Cox knows his Old Norse and so do I. I’m sorry, but it’s game over on that. Here’s some of what little we know of them. And yes, it’s pretty clear they loved their woad tattoos:

Pre-history being what it is, there were many conquests in Scotland. The q-Celtic invaders who founded the Kingdom of Dalriada came from Ireland, and settled in Argyll and the mid-west of Scotland. Fergus mac Erk (Big Fergie) was their first king, and arrived in the 4th century AD. They expanded northward. In the late 8th century, Alpin married a Pictish princess and united the two kingdoms. You might think that this ushered in a period of peace, but history records that their son Coinneach (Kenneth) ravaged Pictland with fire and sword in 843. Why? Nobody knows. Rival kings gaily slaughtered each other. Baron Ravenstone describes the royal line in those days as Succession by Frequent Parricide. It is no more than the truth. Yet one Pictish king did survive and prosper. Forget Shakespeare’s MacBeth. The real version was Mac Bethad mac Findláich, Mormaer of Moray, who ruled wisely and successfully for seventeen years until his defeat in 1057 by the rival king Malcolm.

Meanwhile in the south, the Angles occupied Lothian, which is why The Gude Scots Tongue arose: a robust version of Middle English. Modern Gàidhlig is the rightful tongue of the Highlands and Western Isles. (Though not Orkney and Shetland, where it was never spoken. This did not prevent the Edinburgh Education Dept sending a Gàidhlig schoolteacher to Kirkwall. Sardonic laughter would have resulted.) In the far south-west, Middle Welsh was the preferred tongue in Strathclyde. Dumbarton Castle (in the outer suburbs of Glasgow) was their capital. Independent Strathclyde lasted until 1018, when the royal line perished on the death of the last prince Owain the Bald. Henceforth it became part of Scotland.

Then there were the Normans, who refused to be satisfied with the bloody subjugation of England. They invaded the Borders and Lothian and did their usual castle-building thing. For Scotland this was a disaster. More and more Scots lairds found themselves straddling the porous border, unable to make up their minds whether they were English or Scottish. The result was that when the throne became vacant on the death of Alexander III in 1286, and his granddaughter perished at sea, there were no less than thirteen claimants to the throne. One of them being Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick. All thirteen of them swore fealty to Edward Longshanks, King of the English, asking him to decide who was the rightful king.

Yes, really. (I mean, whut?) You won’t see much of that in Braveheart and Disneyworld. Edward, who was nothing if not conscientious, spent over a year weighing up the rival claims. His choice of John Balliol was irrefutable. The trouble was that (a) Scotland by this point was all but ungovernable, and (b) Balliol had all the executive ability of a blind hedgehog in a thunderstorm. His own nobles deserted him, calling him Toom Tabard (empty coat) and made alliance with France. Edward could not possibly allow this. He invaded Scotland and took the throne himself.

There was some resistance, but not much. Norman lairds changed sides more often than they changed their tunics, because they didn’t want to lose their English lands. But in 1297 an obscure Norman soldier called William de Walys raised the flag of rebellion in favour of Balliol. (Who had already resigned the crown to Edward.) Walys’ revolt ought not to have succeeded, and eventually it did fail. Not before he won a startling victory at Stirling Bridge: a battle worth studying if only to dispel Mel Gibson’s baroque fantasies about it. Walys was a rare and incomprehensible creature by the standards of the day. Scotland for the Scots! was a battle slogan widely regarded as meaningless in the Middle Ages. The best we can say of Walys is that he was a true patriot, in the modern sense. The nominally Scottish Norman lairds were almost to a man self-seeking adventurers, give or take a Douglas or two.

Not least Robert Bruce, who fought for Edward during Walys’ revolt until he conceived the novel idea of taking the throne for himself. Unlike nearly all Scottish kings Bruce had rare talents. He was both resolute and lucky. His victory at Bannockburn was so wildly improbable that no-one could possibly have foreseen it.

Fortunately for Bruce, the English commander (Edward II) was an idiot. Outnumbering the Scots three to one, he penned up his troops next to a bog and would not allow them to deploy. And rather than use his schiltrons defensively, as Walys had done, Bruce used them to attack the English lines. Edward’s weary troops fought with great gallantry; but Bruce was victorious. Despite his excommunication (for killing his rival John Comyn in a church) he was made King of Scots by the Declaration of Arbroath. It is a strange document, and could only have arisen in Scotland. One of its remarkable clauses suggests that said Robert is only our king so long as he supports our interests and fights for our freedom. Otherwise we shall oppose him. It was a clause which the Scots nobility interpreted generously, and entirely in their own interests.

The Dark and Drublie times were a miserable epoch for Scotland. Bruce’s descendants were a pathetic collection utterly unable to restrain the over-mighty nobles. In his histories John Buchan – a proud Scot himself – notes that nowhere in Europe could be found a more greedy, rapacious, cruel and utterly irresponsible ruling class. Eventually the Robertocracy died out, unmourned. They were replaced by the House of Fitzalan, later called Stewart after their role as hereditary royal stewards. The Stewarts served their country far better; but atrocious ill-luck followed them like dogs chasing a butcher’s cart. One James after another wrestled with the nobles, and slowly gained the upper hand.

If you thought the nobles were bad, the Church was worse. The earlier kings had alienated much of the best land and resources to a bunch of predatory foreign priests. This did not endear the Catholic Church to the Scots. When the Reformation came to Scotland it came with all the impact of a runaway locomotive:

John Knox really is the founder of modern Scotland. The Church he founded has become a beacon of sanity, kindness and virtue in the modern age. In his own day it was anything but that. He actually served as a chaplain to Edward VI in England. After Cardinal Beaton burnt Knox’s best friend Wishart, and he served for years as a galley slave of the French, he went to Geneva; learned the odious lessons of Calvinism; and determined to root out every last vestige of Catholicism. His loathing of regnant queens relates far more to Mary Queen of Scots and Mary of Guise than his southerly neighbour. As we can imagine, when his treatise arrived on Elizabeth’s doorstep She was less than amused.

Overnight much of Scotland was transformed into a Calvinist stronghold. Church property was confiscated and shared out. Not of course to the peasantry, but to the clergy, and to those lairds who embraced the new reformed kirk. So matters stood until the reign of Charles I. The Scots tolerated his father, whose sage kingcraft lulled their well-founded suspicions. They even tolerated – only just – his imposition of bishops on them. But they would not tolerate Charles’ crypto-Catholicism nor his new prayer-book. And thus was the Covenant born. It is a fact that the first Covenant’s battle-cry was For King And Covenant. James Graham, Marquis of Montrose, was one of the signatories. When it mutated into Jesus And No Quarter Montrose quit the movement.

If you find yourself in St Giles’ cathedral in Edinburgh, do pay your respects to Scotland’s greatest hero. He was not merely the best soldier of his age. He was a warrior-poet and a deep, clear political thinker. It was his vision of Scotland that endured and eventually flowered. At his execution – ordered by a kangaroo court headed by Johnston of Wariston and other ranting preachers – the mob came to jeer and hoot. So overawed were they by his demeanour that they saw him hanged in silence. His remains were quartered and placed on pikes above several cities. When Charles II thought he could get away with it, he ordered that the remains be encoffined again and carried in solemn procession to St Giles. Some of his murderers were made to carry the coffin.

As a soldier he ranks only with Hannibal. Sent to conquer Scotland by Charles (at least two years too late) he arrived with three broken-down horses and two companions. Charles had promised him troops, but they never materialised. He conjured a small army by sheer force of personality and smote the Covenanters in six pitched battles. Generally he was outnumbered two or three to one, against battle-hardened soldiers led by capable generals. Aside from his Antrim division led by Alasdair Colkitto his only troops were Highlanders who would invariably decamp with their booty after each victory. They ought not to be blamed for that. Their families were utterly reliant on their menfolk to bring home plunder to feed them. But it did mean that on his legendary forced marches he often had less than a thousand men. His only two defeats were more properly ambushes. No general has ever done so much with so little.

The logistics of Highland warfare ensure that the Highlands cannot conquer the Lowlands for long. Yet after the final battle of Kilsyth Montrose was master of all Scotland. Alas for him and his cause, Charles by then had blundered away his army in England. Had Charles the wit to make Montrose his chief commander in 1643 he could have swept the island from Caithness to Cornwall. Not even Cromwell could have stood against him. Would Charles have learned any common sense in that event? We will never know, but the odds are against it, alas.

Between them, Montrose and Cromwell managed to suppress the Covenant. There is little good to be said of this insurgency. They were crazy sectaries whose modern equivalents still torture and murder in the name of religion to this day. Throughout the reign of Charles II they continued to slaughter and pillage, especially in Galloway. Montrose’s nephew Claverhouse suppressed them as best he could. After the Glorious Revolution in 1688 the clans decided to fight on for the House of Stewart. In popular balladry False Claverse magically transmuted into Bonnie Dundee. Nothing had changed. The House of Graham fought, as ever, for the House of Stewart. I will not revisit the Jacobite Rebellions in any detail. You should know the tale of sorrow if you have read thus far. The best of it was that the Highlanders went down fighting to the end.

But Scotland itself was incorporated into the United Kingdom in 1707. Was this a tragedy? I’d say no, but I’m only Scots by distant ancestry. The pointless cruelty England visited on Ireland was largely omitted in the case of Scotland. The Massacre of Glencoe was a purely Scots affair. It was ordered by the Master of Stair. A Covenanter, no less. It figures. Cumberland’s brutality after Culloden was a shameful crime, and utterly needless. However, there was a curious incident during the slaughter of that direful day.

Clan Chattan perished to a man. Last to fall was the giant Giles Mac Bean. His deeds have passed into legend, as is right and proper. Having killed fourteen redcoats he fell at last. A British colonel cried out to his troops: ‘Quick! Someone save the life of that brave man!’

It was too late for him, but the legend of Highland courage and indomitability had begun. There is another curious incident in the Jacobite aftermath. Readers of Stevenson will know the novel Kidnapped. One of the threads is the judicial murder of James Stewart of Aucharn, falsely accused of the murder of Colin Campbell of Glenure. Later King’s Bench reports omit this travesty of a trial, held in Inverary with the Duke of Argyll sitting on the bench. I have in my possession an original copy of the 1762 version, purchased in a Bath bookshop long ago for a mere five pounds. (It also includes the trial of Earl Ferrers, who was convinced that murdering his manservant would be understood by his fellow peers. To a man, they disagreed.) The transcript makes scarifying reading. We can hardly be surprised that all mention of it was later quashed, until Stevenson brought it out into the open again.

So far as England was concerned such tribal squabbling would no longer be tolerated. Overall, Scotland got a very good deal from the Act of Union. The Duke of Sutherland aside, England is guiltless of the Clearances. Scotland has prospered within the Union. The English don’t understand the Scots, but – by and large – they leave this rugged and beautiful land alone. It’s OK to vote SNP. It annoys the English and that is all very proper. But you have to know when to stop. The SNP thinks Scotland ends at Dunkeld and Cumbrae Steps. And please do not romanticize the EU. They are not your friends. Every time you think about seceding from the Act of Union, do listen to Flowers of the Forest and ponder the Battle of Flodden. The Auld Alliance was never your friend. And if you do this, what’s to stop Orkney and Shetland taking the West Virginia option and seceding from you? Unless you’ve been there, you don’t understand them at all. Shetland even has its own flag. It looks like this:

Faero and Iceland are beckoning…..

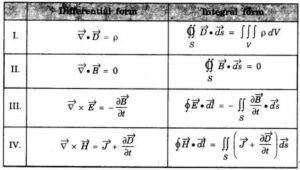

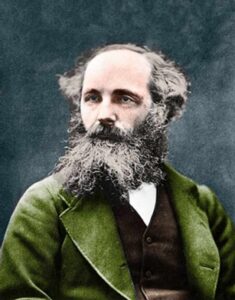

Thus far, I have not even mentioned the Scottish genius for invention. Think of John Napier, who invented logarithms and made calculations massively easier. The true father of the modern world is not Isaac Newton. Without James Clerk Maxwell there would be no electricity:

Much of England’s famous Industrial Revolution was invented by Scots. The English may have forgotten this. The Scots haven’t. Nor should they. However … to understand modern Scotland, I can do no better than to recommend the remake of Whisky Galore (far better than the old black and white version), and Bill Forsyth’s wonderful trilogy of films. Gregory’s Girl, Local Hero, and Comfort and Joy are filled with joy and wonder. Here is Scotland stripped of its tartan tinsel, and standing proud on its own feet.

In conclusion, here is a tale about real Highlanders, in the manner of John Buchan. Rob Roy needs to be rescued from Sir Walter Scott and Hollywood. I have taken a few liberties with history, but Fearchar the Grey Warrior was real. Do not take your mythmaking from someone who knew not a Highlander from a haggis.